----- WHEN WAR CAME TO AUSTRALIA -----

We were in the Winnellie camp for two weeks, just about long enough to recover from the “trots” which everyone had from drinking the bore water on the trip north. The situation with regard to the advancing Japanese was pretty tense, and an invasion was expected at any time, so in the first week of February the Battalion was dispersed into defensive positions around the Darwin area.

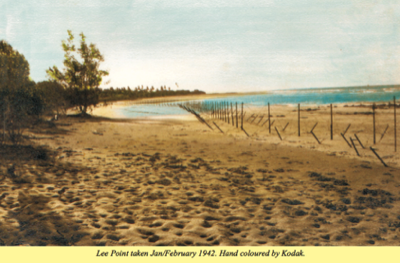

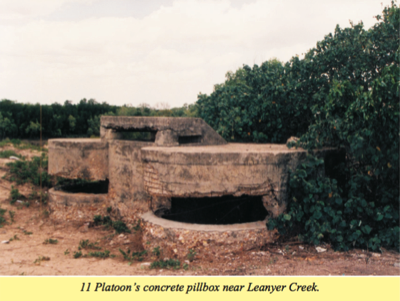

“C” Company was allocated to the Lee Point area, to occupy the concrete “Pill Boxes” which had been installed prior to our arrival. Fred Jones (Major) was our “C” Company Commander. The three platoon leaders were Lt. Harry Watson (11 Platoon), Lt. Bob Greer (10 Platoon), and Lt. Halliwell (12 Platoon). Lee Point is situated 5 miles almost due north of the Darwin aerodrome. Our “C” Company was a force of 120 men with about 5 minutes ammunition and little or no air support, strung out over more than a mile of coastline to defend Australia against an invasion force of 40,000 plus Japanese. Our pill boxes were situated in strategic positions at the edge of the scrub and trees facing the beach and the open sea to the north, and were covered by camouflage nets to conceal them from the enemy. Somebody had decided that the enemy must come up the beach. They were not allowed to land somewhere else, and sneak around the back of the chosen positions, just to avoid being shot. The pill boxes looked like two circular concrete water tanks about 2 metres in diameter, placed side by side. They each had a horizontal slot cut into the side facing the beach, and two Vickers machine guns positioned so that they could fire out through the slots. Behind the gun positions was a small concrete room in which the ammunition boxes were stored. Above and between the two gun positions was an observation post with slots to the front and either side, from which an observer had a forward and sideways view of the landscape.

They were said to be bomb proof, but like most insurance policies the warranty was void in case of acts of war, and/or (and especially if) there were any aircraft in the area. The roof was a slab about 8" (20cm) thick, made of rather poor concrete, which would be useless in the case of a direct hit. A dud 50kg bomb dropped near the RAAF Aerodrome from 20,000 feet altitude left a neat round hole fourteen feet deep, and anyone in one of those pill boxes when it was hit would certainly need a cuppa tea, an aspirin, and a good lie down. Right along the beach front were barbed wire entanglements which in WW-1 when they were designed, may have seriously deterred foot soldiers for some considerable time. One of our problems in WW-2 was that our entire war effort was based mostly on WW-1 experience which was totally inadequate and outdated for the type of war we had to fight, and the barbed wire in this instance would have hindered us more than it would have hindered a Japanese landing party. The beach was sandy, and extended for about a mile when the 25’ tide was out. When the tide came in, it brought with it tree branches, logs, and all matter of debris which caught in the barbed wire entanglements and pounded hell out of them. One of our daily tasks was to repair the wire.

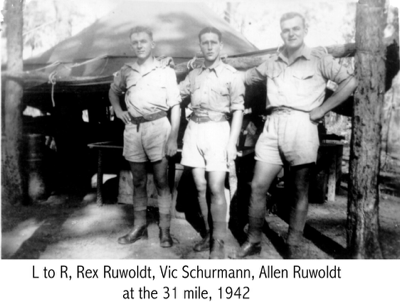

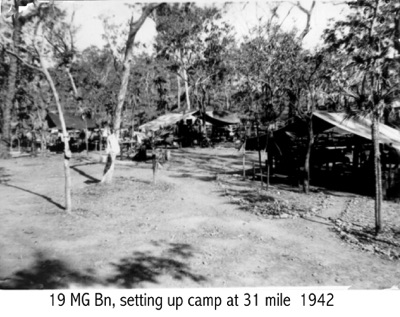

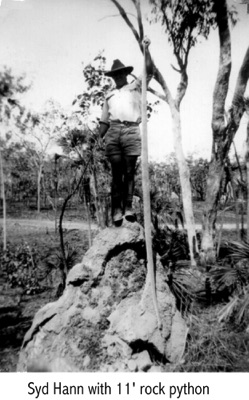

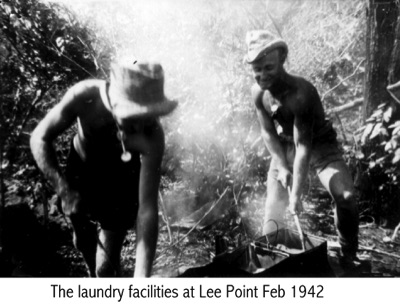

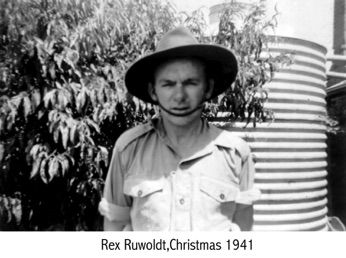

The living conditions were somewhat less than one would have expected at the Hilton. Tent fly’s which the Army had saved from WW-1 were strung between the trees, and we slept under mosquito nets, four to a tent fly. Rough stretchers were made up by cutting the bottom corners out of two chaff bags, and slipping them over two straight saplings cut about 7’ (2 m) long; these were then supported on stakes driven into the ground to keep the stretcher a foot or so above the ground. There were millions of mosquitoes, spiders, and creepy-crawlies of all description, including scorpions as big as yabbies, and plenty of centipedes up to 6" (15 cm) long. If you stayed in the shade under the trees, the mossies ate you alive. If you went out on the beach, the sandflies took over. Precautions had to be taken; shake out your boots and helmet to make sure there were no centipedes or spiders etc. in them before you put them on. White ants too could do a lot of damage; they would eat the soles off a pair of boots left under your bunk for more than a few hours at a time. The centipedes were nasty. They are said to be not toxic to humans, but their bite is extremely painful. Allen Ruwoldt put on his steel helmet one night to go on guard duty, and was bitten on the back of the head. In the early hours one morning, Les Sudoltz, who slept under the same tent fly as I did, gave out a horrible gasping “Arrrrgh!” which sounded as though someone had run a knife through his ribs. I grabbed my rifle and bayonet, ready to join the fray, when Sudy struck a match and started swearing. “*!*x?##!**?centipede!”. Les and the centipede both lived to fight and bite respectively, for another day. The centipede got away, and Les got experience - very painful experience.

Toilets were holes in the ground; bathing initially was a swim in the estuary of Leanyah Creek, until one day we found a fourteen foot crocodile sleeping on the bank waiting for his dinner. After that, we swam in the surf when the tide was in, until a shark shot out of a wave and gave us one hell of a fright, so we finished up staying in the shallow water. Guard duty fell to all the non-commissioned ranks - every night it was two hours on and four off for everyone, with bayonets fixed and a round up the spout. (Sub-title for those of elegant upbringing - the rifle was loaded!). The signal for a general alarm was three shots in succession. One shot fired in the night was the signal for the onset of nervous jitters, and a check to see what the hell was going on. At two o’clock one morning, when the guard had just changed, a shot shattered the stillness of the tropical night, and everyone was awake in a flash. Investigation revealed that one of the 11 Platoon guards (whose name will be suppressed to protect the innocent [me] from the guilty), being half asleep at the time, had taken his rifle and gone on duty inside one of the pill boxes. It was a dark moonless night, and inside the pill box it was absolutely pitch black. He loaded his rifle, but he held the trigger back when he pushed the bolt home so that there would be a round up the spout, but the hammer was not cocked. When a Lee Enfield .303 is loaded in this fashion, the firing pin rests on the firing cap of the cartridge, but it reaches that position gently without sufficient force to fire. He then realised that he had forgotten to fix his bayonet, so he pulled it out of its scabbard with his right hand, and holding the end of the barrel with his left hand, as he normally would, he proceeded to fix the bayonet. Being half asleep in the pitch darkness, he waved the rifle around somewhat, and struck the hammer on a concrete step. The rifle fired, and the bullet entered the fleshy part of his right hand at the base of the thumb near the wrist. It came out at the base of his thumb, ploughed a groove in the side of his thumb from end to end, covered the open wound liberally with burning cordite, and went on its way at a speed of 2450 feet per second. As it hit the concrete roof of the pill box, chunks of concrete flew in all directions, and he flew out of the door. “Christ!” he said, “It’s a good job I got out before the ricochet got me!” It was about 57 years later that a lady rang to tell me that her husband wanted to join Darwin Defenders. I asked her "Wasn't he the chap that accidentally fired his rifle inside the concrete pillbox?" "Yes" she said. "He did. Then he went to New guinea and blew up a cook house. So I wrote to the Army for a copy of his war record, because I wanted to find out which side he was on!" That one rifle shot weakened the concrete roof, and while it survived for over 60 years, a few months ago the Darwin Council demolished it in the interests of public safety.

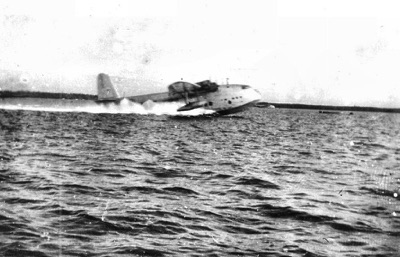

Allen Ruwoldt was the Despatch Rider (known as the “Don R”) for “C” Company, and Ernie McMullin was the “Don R” for “B” Company. Don R’s were equipped with an English Norton motor cycle capable of at least 40 MPH, and in those days before portable radios had become available, they were the fastest means of communication in the field where there were no field telephones. Ernie was on guard duty at about three o’clock one morning, when he saw a strange light approaching from compass bearing three six zero degrees, which was straight out to sea to the north. Instructions were that any strange occurrence was to be reported to Head Quarters immediately, describing what it was, and the compass bearing from the guard post. Ernie grabbed the telephone, and quickly called HQ, and HQ answered: “Major Blackwell here!” “Sir! There’s a strange light approaching from three six zero degrees!” “Did you go and investigate it?” “No Sir! It’s at three six zero degrees!” “Well why the hell didn’t you go and investigate it?” “Look Sir!” said Ernie in exasperation, “I’m a Don R, not a Donald Duck!” By the time the argument was finished, the emergency was over. The lights were the landing lights of a Sunderland Flying Boat which wanted to land in Darwin, but did not know the appropriate password which was changed every day. As a security measure, Darwin was completely blacked out at night. Complete radio silence was maintained and no landing lights were turned on for any aircraft if the pilot could not satisfactorily identify himself. The pilot’s options were rather sticky. He could go somewhere else and ditch out of fuel, or try to convince Darwin of his identity before they turned the guns and searchlights on him, so he switched on his landing lights as a sign of good faith, kept his radio on, and kept on talking. Fortunately someone must have believed him, and he was allowed to land. Passwords were necessary, but they sometimes the cause of some confusion, especially when people who had to know the password were not told what it was.

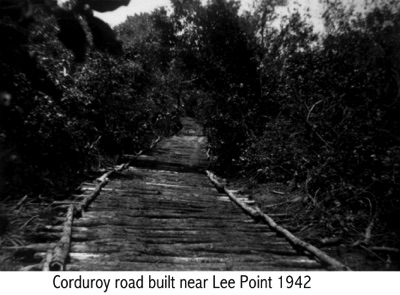

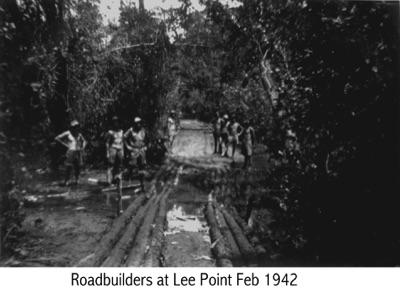

When we arrived and took up our positions at Lee Point, our vulnerability to attack from the rear was obvious, so it was decided to run barbed wire entanglements around the rear of our positions to offer some protection. In a few days the wire was finished, and guards posted at the entrance with instructions that anyone who could not give the password was to be refused entrance. Behind our positions were a battery of artillery guns. Mostly artillery were in a rear position where they could not see the target, so in a forward position they had an Artillery Observation Post (Arty O’Pip for short) which was connected to the gun positions by field telephone, and from which they could direct the fire. (“Right five degrees-up two hundred yards -” etc.) Unfortunately, on the day the wire was finished, nobody told the Artillery Officer the password. Eventually, he came along as usual on his way to his observation post, and was challenged by the guard. “What’s the password?” “I don’t know any password.” “In that case, you can’t come in!” “But I’m Arty O’Pip!” said the Officer, “I’ve got to come in!” “Look mate!”, said the guard, “I don’t care what your name is. If you don’t know the password you CAN’T come in!” Eventually the guard was convinced he should call his superior officer, and our friend Arty was admitted to his own position. Shortly after we arrived at Lee Point, on February 8th, the Japanese attacked Singapore, and a week later, on February 15th, Singapore surrendered. Ambon was also taken, and Darwin was within reach of the Japanese land based bombers. “C” Company were not left in their positions at Lee Point for long after the first air raid. As defence positions they were poorly situated and virtually useless, so we were moved to the RAAF aerodrome in a ground defences role, situated adjacent to the southern end of the north/south runway, where we could help to protect the Hudson bombers and the P-40 fighters which were being brought into the area. There was very little activity from the Japanese immediately after the first raid. On the 4th March, two planes strafed some workers at the four mile position, then there was no further enemy activity until 16th March. The RAAF had based their Hudson bombers on the RAAF airfield, and the USAAF sent their 49th Fighter Group equipped with P-40s (Kittyhawks) to build up our defences against further raids. With the fighters, the Yanks sent a contingent of .5 Browning Anti Aircraft gunners, who dug in near us.

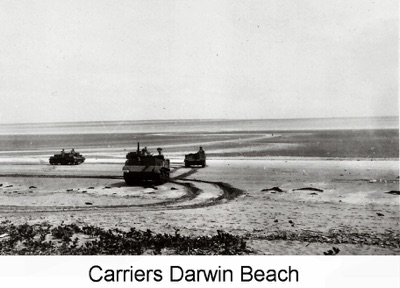

By this time, we had settled into our new positions, and because we were now occupying one of the prime target areas, we had to dig slit trenches, and pits for our equipment. The ground was hard, and the digging was tough. We received an allocation of Bren Gun Carriers which had to be dug in too. There was some indecision about exactly where we should be placed, and after our trenches were dug, we were told that we were to be spread out more, and some of us would have to move across the road a hundred yards or so. The late Jika Pilmore (may God rest his soul) was normally a cheerful mild tempered man, but this made him furious. “I have dug one trench”, he said, “and I’m going on strike! I am not going to dig another trench as long as I well live!” It was a cloudy day. We were all lined up for mess parade, when without any warning, fourteen bombers which had approached unseen started dropping their bombs on the RAAF close by. Needless to say, we dispersed rapidly. Speedy Gonzales would have been trodden underfoot. When we reassembled an hour or so later, Jika was missing. Someone asked: “Where’s Jika?” “He’ll be along presently. He has nearly finished his new slit trench!” The Japanese were back, with a vengeance. They raided the RAAF on the 16th March, Darwin on the 19th, Darwin and Katherine on the 22nd, the RAAF on the 28th and again on the 30th. On the 31st March, they made their first night raid, on the RAAF, at about 10.30 pm. I was sound asleep when the siren went, and I remember that in the panic I had great trouble putting my trousers on. When I had taken them off, I had pulled one trouser leg inside out, and I was hopping around with one leg on and the other foot stuck for some time before I realised what the problem was. On April 2nd, the oil tanks at the harbour were bombed. On 4th April (I think it was Easter Saturday), the bombers were back again, with their fighter cover. I remember this day particularly, because it was the first time a successful counter attack was launched against the Japanese in the Darwin area. The skies were clear. There were seven bombers, in a single vee formation, their colour shining silver against the blue of the sky. As they came into range, the 3.7" Ack-Ack battery near us opened fire. We were told afterwards that the man on the rangefinder called “22,000!” The man setting the time delay on the shells before they are loaded into the guns set them at 20,200’. If this was intervention on the part of the Good Lord, He was definitely on our side.